It gives me great pleasure to share another guest post with you this week:

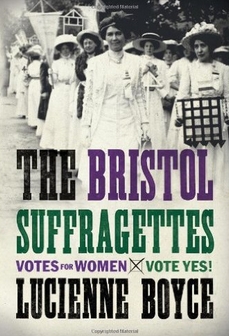

Lucienne Boyce is a historical novelist and historian based in Bristol, which is the inspiration and setting for much of her writing. She has published three books with SilverWood. To The Fair Land (2012) is an eighteenth-century thriller set in Bristol and the South Seas, and Bloodie Bones: a Dan Foster Mystery (2015), set near Bath, introduces Bow Street Runner and amateur pugilist Dan Foster. The Bristol Suffragettes, a history of the local suffragette campaign, was published in 2013.

Lucienne Boyce is a historical novelist and historian based in Bristol, which is the inspiration and setting for much of her writing. She has published three books with SilverWood. To The Fair Land (2012) is an eighteenth-century thriller set in Bristol and the South Seas, and Bloodie Bones: a Dan Foster Mystery (2015), set near Bath, introduces Bow Street Runner and amateur pugilist Dan Foster. The Bristol Suffragettes, a history of the local suffragette campaign, was published in 2013.

Find out more at www.lucienneboyce.com

Bloodie Bones: a Dan Foster Mystery

She is very generously giving her time to speak at the Bristol Book Bazaar on 17th October as part few Bristol Festival of Literature. I’m really looking forward to her talk on researching for historic fiction.

Tickets are available now from Bristol Ticket Shop

Imagination in the Archives

Whenever I’m asked what is the single most important research tool the historical novelist can have I answer: imagination.

It’s not that practical research skills don’t matter. It’s necessary to know how to use libraries and archives, what to avoid if you’re using internet resources, where to see buildings and weapons, costumes and cutlery…In short, how to access the information you need if you’re writing a historical novel.

But I think that writers can get too hung up about research. They fret and worry about “accuracy”, and strain themselves to track down every detail. They’re so afraid of giving a wrong impression or of missing something out (all important considerations) they lose sight of why they’re doing the research in the first place.

And so their research takes on a life of its own. They amass folders full of notes, a reading list that stretches to the moon and back, and a constantly expanding list of “things to look up”. Now they’ve got their “research” on the one hand and their “novel” on the other and they’ve no idea how to join the two together.

I believe that it’s imagination that unites these two aspects of creativity. You don’t just need your imagination when you’re writing the novel. You need to take it with you into the reading room.

Who are your characters?

For example, what you need to know all depends on who, when and where your character is, and what you think is going to happen to them. If you’re writing a story set in war time but your protagonist is a non-combatant, there might not be a lot of point spending hours researching military costumes.

Or you might have only the vaguest idea about your character when you begin. Say you’ve got as far as thinking you want to write about a monk in twelfth-century Shrewsbury, but that’s all you know of him so far. Yet even that bare outline is enough to guide and direct your research. What kind of people became monks? At what age? Might they have had other life experiences before entering the cloister?

As the characters and their stories develop, so your research will expand to accommodate them. But that doesn’t mean you can’t keep your research focussed. Always keep your characters in mind. Try to picture them in the situations you’re reading about. Pick out the details that are most important to them. Don’t just notice what people wore: ask yourself, what would my character wear? Would she or he personalise their outfits, set trends, dress to impress, dress to shrink into the background?

What’s the plot?

If you’re writing a love story, you’ll need to know about things like the relative positions of men and women in society, or if homosexuality was a crime, or if love across the classes was possible. If you’re writing a war story, you need to know about tactics, uniforms and weaponry. If it’s a history mystery, you’ll need to know about the law and investigative methods of the period.

Keep an eye open for the information that will help drive your plot forward. Ask yourself: will this fit into my story? Will it be there for a purpose or will it just be padding?

What kind of story are you writing?

How you approach your research will depend on what kind of story you’re writing. Do you want people to learn about history from your book? Then historical accuracy will be important to you, and you’ll be drawn to events and settings for which reliable records exist.

Or perhaps you find the concept of discoverable “facts” questionable: records are always biased, incomplete or missing. So you may not accept everything you’re told; you may question eye witness accounts; you may choose to focus on one aspect of an event rather than another.

Or perhaps you want to defend a famous historical person. Richard III is someone who many writers want to portray as something other than the villain history – and Shakespeare – has painted him to be. Hilary Mantel gives us a different perspective on Thomas Cromwell in her books Wolf Hall and Bring Up the Bodies. If this is the kind of book you’re imagining, you’ll be looking for as many different perspectives on that individual as you can find.

Perhaps you envisage your story as an alternative history, like Alison Morton’s Roma Nova series (a Roman colony has survived into the present day). In that case, you’ll be on the lookout for a viable turning point – for the moment when everything is capable of change.

The interesting nugget

One of the dangers of letting research take precedence over imagination is the temptation to include in your novel information that isn’t relevant to the story or the characters. This is an area in which many historical novelists fall down. They get so carried away by all the research they’ve done they think they have to put it all in their book. The result is a story that gets bogged down in detail, goes off at a tangent, and loses pace.

But taking your imagination with you when you do your research could help you avoid this pitfall. Keep bringing everything back to your novel. If you stumble on something interesting or exciting that’s not at all connected with your story, not at all relevant to your characters, or won’t fit into your plot – and you may have to think about it for some time before you’re certain – then squirrel it away for possible later use. Nothing is ever wasted. The more you know about the period you’re writing about, the better your writing will be for it.

Whether you’ve written one draft, no draft or a dozen drafts, your research is all in the service of your yet-to-be-created novel. Hold it in your mind as you work and you’ll find it easier to stay focussed. Just as it’s imagination that makes a story, it’s imagination that drives the research. That’s why I believe the most important thing a historical novelist needs for doing research is imagination.

Lucienne Boyce will be talking about researching the historical novel as part of Bristol Literature Festival’s Book Bazaar & Writing Seminars on 17 and 18 October 2015. For further information see http://unputdownable.org/news-updates/2015-events-announced

Find out more about Lucienne’s work on her website: www.lucienneboyce.com

Stay up to date with her on Twitter: @LucienneWrite